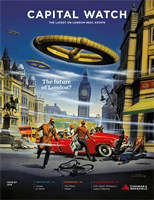

They can also adapt to unforeseen

events, (such as someone getting

in the way of a defined path) which

is what is unlocking the adoption

of autonomous vehicles, and many

other new innovations. This provides

an exciting step forward in human

progress, potentially unlocking

advances that were previously science

fiction. However, it will also create

significant disturbance in existing

industries.

The Oxford Martin School have

produced a paper which sets out

those industries most susceptible

to automation, and the results may

surprise some. It is not necessarily

low value functions that will be

removed, like in the 1980s. The

degree of susceptibility depends on

a human’s relative advantage over AI.

Even matters requiring considerable

intellect are, if process ladened,

potentially replicable and quite

possibly bettered by an AI. As Dr Carl

Frey noted in his talk at our Future

of Work Conference, a computer is

free from the bias, heuristics, and

hangovers that afflict humans. For

accuracy and predictability, pick a

robot. Perhaps consequently it is

those jobs that in fact require the

subjective biases of creativity and

social intelligence that are better

protected. Hence a hairdresser may

be less susceptible to automation

than an accountant.

So is this a good or a bad

thing? Again, it depends on your

perspective. History tells us that those

who own the machines that facilitate

change are going to get rich at the

expense of those who don’t. In an era

of declining real wages, this is only

going to exacerbate the inequality

of wealth in our already polarising

society. However, this is not the whole

story. Although much reference is

paid to the poor conditions and long

hours of workers in the industrial

revolution, it was precisely this ability

to work long hours and gain wealth

that lifted many workers out of

agricultural poverty. Secondly there

is the ‘Luddite Fallacy’. This suggests

that new technology does not reduce

employment, it merely changes its

composition. Innovations reduce

costs; they also create demand for

new goods and services. Jobs find a

new home, although not without a

reskilling lag, which is why education

will be so important in the years to

come. And finally, in the first industrial

revolution someone was needed to

build the looms and the factories.

That is where the property industry

comes in.

Property is an incredibly capital

intensive industry where costs are

amortised over many years. In this

context, unexpected technological

obsolescence is a huge threat to

value. If you owned a new office

building in the 1980s built to a pre-

digital spec, and suddenly there

was a requirement for new service

media that necessitated an increase

in the slab-to-slab height, you

were faced with an instant write-

down. An anticipated move to fully

automated / robotised industrial

space will consolidate the change

in this sector started in the 1980s.

Generally, one might assume that the

offices and shops of the future will

be differently dimensioned, scaled,

and specified than they are today.

Potentially new assets and sectors

will be created. Previous revolutions

created cities; the current one might

now start to rip them apart. If so, a

value model focussed on investment

concentration will come under threat.

More likely is that over time cities

will be repurposed. Meantime, there

has never been a greater need in

recent times to build flexibility into

development projects and watch

carefully those industries that are

being unlocked, and those that are

being diminished. And for all of us on

a personal level, there can be no room

for complacency.

There has never

been a greater need

in recent times to

build flexibility

into development

projects

It is not

necessarily

low value

functions

that will be

removed, like

in the 1980s

Tesla’s self-driving car

Robotic workers

CUSHMAN & WAKEFIELD

20

FUTURE OF WORK